Discover HKBU

Documenting Hong Kong's medical past

23 Jun 2023

While "quarantine" and "social distancing" have become highly searched keywords in the past few years, the practice of such public health precautions in Hong Kong dates back to the 19th century, according to the historical records of the city’s medical landscape. How did infectious diseases impact the development of Hong Kong’s medical system?

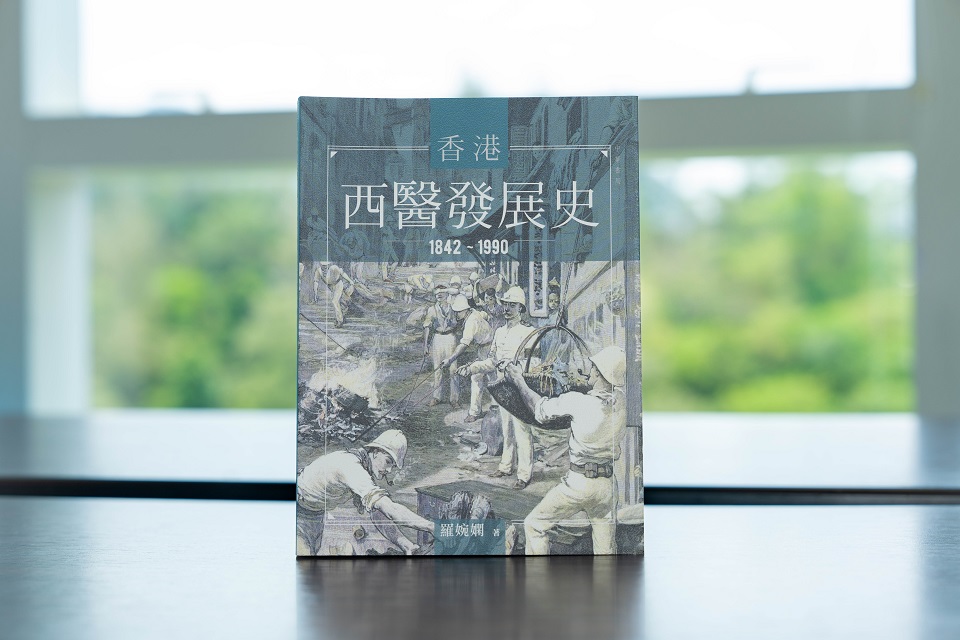

Dr Law Yuen-han, Lecturer I of the Department of History, examined the data from various sources including government gazettes and colonial medical reports, and penned the book History of Western Medical Services in Hong Kong, which chronicles the history of the city’s medical practices. “Every epidemic outbreak or medical policy has profound social implications. Studying the history of medicine is not only about increasing our knowledge of the past, but it is also closely related to the way we live in the present,” she says.

A milestone in Western medicine in Hong Kong

Hong Kong’s healthcare services are widely recognised in the world and are ranked among the best in Asia, and the reason is revealed in the city’s history of medicine. “Hong Kong is in a unique position where our society is predominantly Chinese, and yet the standard of Western medicine here is recognised internationally. From my studies, I found that the outbreak of the bubonic plague in 1894 was a turning point in the development of Western medicine in the city,” says Dr Law.

The 1894 plague, a significant event in the history of Hong Kong’s medicine, was a deadly outbreak of bubonic plague which spread through the Chinese community, resulting in a mortality rate of 95%.

Dr Law discovered that Chinese people at the time deeply distrusted Western medicine, and therefore resisted the measures which were used to control the spread of the disease. For example, some infected individuals pretended they were not ill to avoid being inspected or quarantined, while rumours were going around about patients getting killed after being taken to the hospitals. These reactions prompted the government to reform its medical policies after the plague. Western clinics in different districts were then set up, and Western childbirth practices as well as maternal and child health services were introduced. As a result, the Chinese community gradually accepted Western practices, leading to their popularisation in Hong Kong.

Dr Law believes that studying the history of medicine is very meaningful. In her research, she discovers how people would believe in rumours, use folk remedies or panic buy amidst virus outbreaks. From the 1894 plague to the outbreak of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in 2003 and the recent coronavirus pandemic, these menaces show the irrationality of humans’ reactions in face of the threat of death. “Besides studying the implementation of healthcare policies, research on the history of medicine unveils social practices and changes through people’s personal stories. In recent years, the government’s promotion of the development of Chinese medicine, along with the trend of Chinese and Western medicine collaboration, both promise to bring new changes to Hong Kong’s medical landscape,” she says.

Tracing the history of nursing education

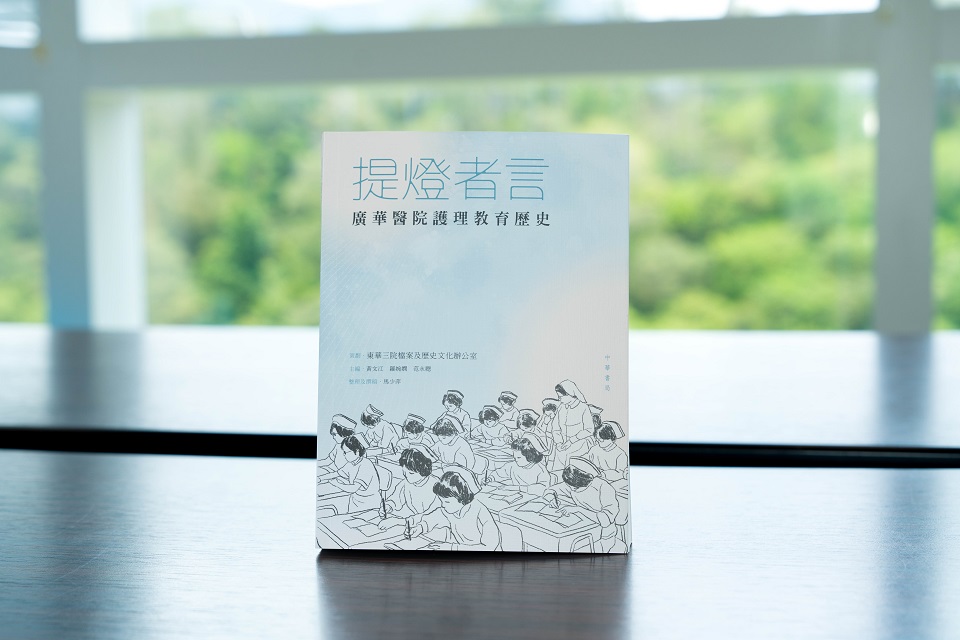

Nursing education plays an important role in the development of medicine and healthcare in Hong Kong. In collaboration with Professor Wong Man-kong, and Dr Fan Wing-chung, Senior Lecturer of the Department of History, Dr Law carried out a project about the history of nursing education at Kwong Wah Hospital. The project also featured interviews with 24 retired nursing staff who joined the profession from the post-war period to the 1970s. The findings of the project are published in the book Nursing Education at the Kwong Wah Hospital and the Everyday Life History in Hong Kong: An Oral History.

History students at HKBU and secondary school students conducted oral history interviews and prepared the transcriptions of the oral accounts. Dr Law says: “We hope that young people can learn how to apply oral history methodology in research, and gain a deeper understanding of the development of medicine in Hong Kong as well as the professionalism of the nursing staff.”

Elaine Wong, a Year 4 student, guided the secondary school students in developing the interview questions and drafting the reports. She also contacted and interviewed the retired nurses. She finds it rewarding to be able to get these firsthand accounts of history. “Taking part in the oral history interviews has brought me closer to history,” she says. “I am used to doing a literature search for my studies, but this project has challenged me in new ways. Based on the nurses’ narration of their personal stories, I was able to get a better understanding of what they went through and how it related to the course of history.”

Elaine is particularly moved by the nurses’ sense of mission. She recalls an incident, told by one of the interviewees, where the nurses of the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals called for equal pay, on par with what their counterparts were earning at the government-funded hospitals. On the eve of a planned sit-in protest, there was a landslide on Hong Kong Island, and the nurses immediately cancelled the sit-in and returned to work to help the injured. Soon after the incident, the government accepted their request for fair pay.

In her analysis of the evolution of the nursing system, Dr Law found that many of the nurses who joined the profession in the 1950s and 1960s were single. She says: “Traditional values prevented married women from entering the workforce, and therefore hospitals discouraged nurses from marrying to avoid staff shortage. Married female nurses were not offered permanent contracts or promotion opportunities. In addition, most people then knew very little about the work of nurses, and male patients refused to let female strangers look after them.” Dr Law hopes that the book can shed light on the development of Hong Kong’s nursing history and nursing education, and help readers better understand the challenges faced by the nurses, who tirelessly served the public behind the scenes, in Hong Kong’s early years.