Discover HKBU

The art of learning poetry through theatre

28 Mar 2023

How do you get young students interested in reading ancient poetry? Maybe ask them to help solve a murder mystery.

Classical poetry, the jewel in the crown of Chinese literature, has a rich cultural heritage, yet most students today find it difficult to understand the ancient language. Moreover, simply memorising verse barely helps with interpretation of its poetic meaning. Taking an innovative approach, local drama troupe Alice Theatre Laboratory launched the “Jockey Club Theatre-in-Education Project on Legendary Stories of Chinese Poets” (the Project), funded by The Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust, from 2019 to 2022.

The Project utilised the methodologies of theatre-in-education and drama-in-education to promote the appreciation of classical poetry among primary and secondary school students and enhance their language skills through lively dramas. To evaluate the impact of theatre-in-education, Dr Tong Yui, Associate Professor of the Department of Humanities and Creative Writing, was invited to become principal investigator of the Project. He also shared his knowledge of Chinese language and literature with the drama troupe to help them devise teaching resources.

Using drama to teach poetry

The Project delivered 165 theatre-in-education sessions over the past three years, with the participation of around 170 teachers and more than 6,600 students from 64 primary and 13 secondary schools. Mr Andrew Chan, Artistic Director of the Alice Theatre Laboratory, explains that drama-in-education is not the same as teaching drama. “It is about using drama as an educational tool to teach a number of subjects in a way that helps and motivates students to learn,” he says. “Theatre-in-education, on the other hand, contains a strong element of interactivity. Students are encouraged to participate through role-play and apply the knowledge they learn to help the characters solve challenges.”

In the Project, teachers from participating schools first received eight hours of workshop training. They then worked with the drama troupe’s actor-teachers in leading the theatre-in-education sessions. This allowed students to explore the lives and works of ancient and contemporary Chinese poets, as well as their relevant histories, and learn how to write poems.

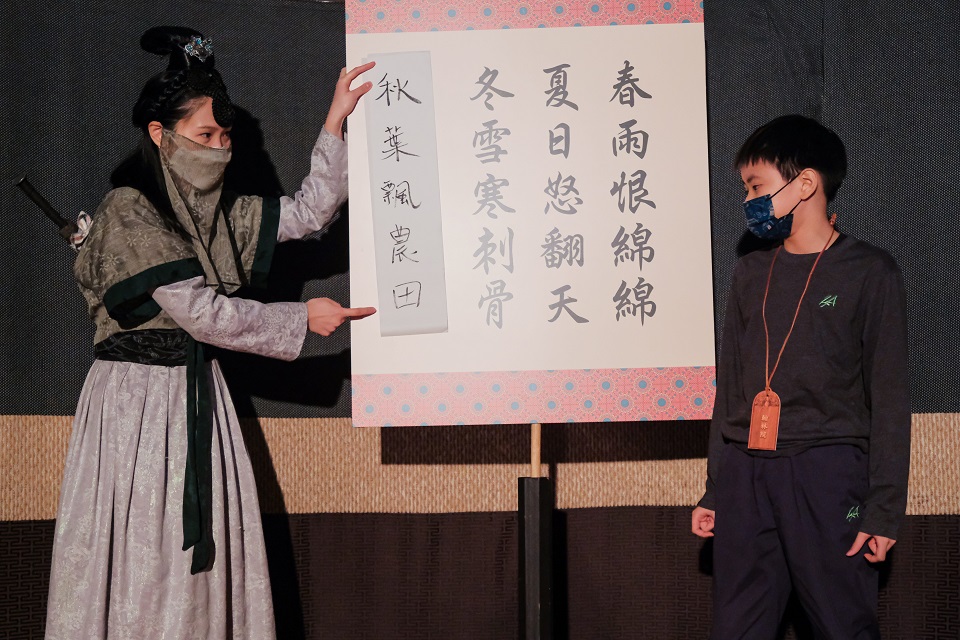

The theatre-in-education sessions for primary schools involved a poem completion game. Set in the Tang dynasty, the production engaged students to act as prospective academics of the Hanlin Academy, which was lorded over by a corrupt eunuch. To escape from harm, they must create a poem. In the process, they studied the works of legendary Chinese poets such as Li Bai and Du Fu, the principles of poetry writing, as well as the history and culture of the Tang dynasty.

Meanwhile, junior secondary students took part in contemporary poetry writing activities where they played the role of detectives investigating a murder case. They learned about modern poets such as Xi Xi and Yesi, and were tasked with applying poetic aesthetics to create a contemporary poem in five minutes.

Inspiring curiosity to appreciate literature

During the Project period, Dr Tong and his team at HKBU conducted onsite observations, questionnaires and interviews at schools to assess the students’ language proficiency as well as their literary, historical and cultural knowledge. The team also looked into changes in the students’ moral sentiments and attitudes towards learning.

The study found that around 90% of the students believed the sessions helped them better understand poems, and over 80% felt more assertive about their capabilities to learn and appreciate poems. Moreover, they gained self-confidence through performing and became more open to expressing their views. The HKBU team also observed that some students with special educational needs or who perform weakly in traditional curriculums actively participated in the theatre-in-education sessions. Dr Tong says: “One student hadn’t turned in his Chinese homework all year, but after participating in the sessions, he took the initiative to write a poem on his own. Similar cases were found in other schools as well. Theatre-in-education helps students build self-confidence, and this encourages them to participate.”

Dr Tong believes that the Project not only enhanced students’ understanding of traditional culture and inspired them to study literature, but also held a special significance to the drama troupe and the HKBU team. “The Project brought together a group of people who shared the same aspirations, and each one of us contributed our knowledge and skills to give back to society and make a difference,” Dr Tong says. “At the same time, we sought to innovate by introducing the drama-in-education pedagogies, which are hugely popular overseas, to local communities. We also took into account Hong Kong culture and the needs of the community when developing localised teaching techniques and materials.”

He adds that the Project broadened the horizons of the HKBU students in his research team. Through participating in the study and visiting different schools in various communities, the students got to know how theatre-in-education works and gained first-hand knowledge about education in Hong Kong. Some students also developed an interest in teaching and became teachers after graduating from HKBU.

Dr Tong hopes that the teachers who participated in the Project will continue to apply drama-in-education techniques into their teaching to reinforce its impact. The team also plans to develop new drama-in-education programmes to teach other types of Chinese literature and attract more students to participate.